The following song was composed especially for the Sixth Annual Retreat of the Protestant Fellowship of Maridi Institute of Education, Khartoum, Republic of Sudan, February 25-27, 1963.

Phyllis Jessie Webb, 1963

I was born in the west of London just before World War I started. My earliest remembrance is that of being carried downstairs in the middle of the night, as the bombers came over and my mother and my grandmother would hide us under the dining room table. We would make a game of it so that I didn’t really remember the war as something terrible, rather having fun and games in the middle of the night. Sometimes as we went for walks in the park, I would see places where houses had been, so that I realized how very bad the war was in our neighborhood.

My Father had gone to the Middle East during the War, and I didn’t know him at all. When he came home at the end of the War, I was quite afraid of him. He had been a family of just women and children, and I was afraid of the father, who, of course I learned to love very much afterwards.

Some of the earliest memories I have, are of a woman who used to come along the road every Sunday and wave to us. One day she stopped and asked if we would like to go with her to the Sunday School down the road. Mother was very glad for us to do that, so we went to this Sunday School on Sunday afternoons, and later to Sunday School in the morning and Church in the evening. Sunday was all Sunday School and Church and we learned a lot of the Bible and many, many hymns and choruses about Jesus, with my mother always praying with us. I came to love Jesus very much and to realize He was my Savior.

One day, the Sunday School teacher in the morning told us about Mary Slessor, who was a missionary in the west side of Africa. She had rescued twins who were thrown

out to the hyenas. The people believed twins had an evil spirit in them, because they were something very unusual. So, all twins were put outside the village for the hyenas to eat.

I was so moved by the thought of these babies being eaten by the hyenas, that, as she was telling us the story, I felt God was very near, that His hand was on my

shoulder. I heard Him say, “I want you to go to Africa when you grow up. I want you to be a missionary, too.”

So, I went home and I told my mother I was going to be a missionary in Africa. She told me I’d have to be a very good girl and that I would have to study very hard.

From then on, I knew that I had to be a missionary. We were a good, strong, Christian family, but no one had been a missionary before my commitment.

I had an aunt of whom I was very fond (actually, a great aunt) in Wales. She was very influential in my life because, when she would come to visit, she would talk to us about Jesus and about the work that she was doing in the mountains of Wales. She was a nurse and a midwife, and she would go at any hour of the day or night to help women who were in distress delivering a baby. She did become an influence in my life, because that is exactly what I did in Africa later on. It was her influence that caused me to take up nursing, to become a nurse and midwife, and to go to Bible College to prepare to work in Africa.

My training is a story in itself.

When I was in school, I used to work very hard; always came very near the top of the class because I really did believe I had to work hard to become a missionary. When I had finished grade school and high school, I didn’t have any money to get the training I needed. Our family was five children by that time. The educational system is very different in England. I did win a scholarship to get the Secondary Education I needed, but most girls and boys of my day left school when they were seventeen and started to work. The opportunity came for me to get a job as a secretary in a large biscuit firm, (Cookies in America) McVitie & Price, where I learned office skills. God was still leading me, because in that firm, in that great office, there were two managers who were Christians. They encouraged me to continue my education and of them blessed me before the large office staff.

When the time came that I felt I should start some kind of training, I went to see our vicar in the Church of England. He said, “Being a missionary isn’t for people like you. You need a great deal of education.” I was educated as far as our class of people, but I needed a University Education, which was only available to the very wealthy. He said the same thing to Alan, who was later my husband. Both of us wanted to be missionaries.

Around that time, I had a bad case of influenza. I spent time sitting by the fire and I read the Gospel according to Matthew, 3:13, the verse where Jesus was baptized. John said he needed to be baptized of him; he realized that Jess was greater. Jesus said, “thus it becometh us to fulfill all righteousness.”

I was convinced that God was telling me that I should be baptized by immersion.

I’m sure that this was God’s leading me. This was a step of obedience I had to take. Strangely enough at that same time, Alan, who was at the Missionary Training

Colony, had the same inspiration, because in Africa nearly everybody is baptized by immersion. I didn’t know this at the time. This was definitely the Lord speaking to me, “This I want you to do.”

I went to see the Baptist minister. I told him what had happened, that I felt constrained to do just as Jesus did, to be baptized by immersion. “Thus, it becometh us to fulfill all righteousness.” That was all

I knew. He asked me several questions and made sure that I really did believe in Jesus.

The day came and I was baptized. I never will forget the experience. I was so tremendously full of joy;. as though the Holy Spirit had really come and possessed me. As I walked out of the church the people

gathered around, all strangers to me. It was a different church - a Baptist Church (not the Church of England. MB). Still, the people gathered around me to welcome me, and I was so full of joy I felt as if my

face would burst! I had taken a step of obedience.

I didn’t know it at the time, but the Baptist Minister was on the Board of our local hospital. The matron at the hospital agreed to take me on trial, because of his recommendation. In addition to the drawback of my class, the hospital never took local girls. They took girls from as far away as Ireland. Because, they said, when you met friends on the street they would ask questions about patients, and a junior nurse shouldn’t tell people what was happening in the hospital. So, God was over-ruling in all these things.

It was hard work. A twelve-hour shift with two hours off when we had to take lectures. We almost never got out of the hospital.

My mother, of course, was close by, so I could see her. But none of the other nurses ever saw their parents.

It was hard, hard training, very hard training. But I thank God for every bit of it, because I used it all. When I finished training, I passed the State Boards with very high grades.

The next step was Midwifery. I didn’t feel I was ready to go to Africa without the Midwifery training. It was one of my most wonderful, inspirational experiences.

In the meantime, I had become engaged to Alan Webb. He was three years older than I, had finished his training, and was already out on the field. It meant that he would have to wait that much longer while I took this extra training. But I felt very strongly that I should.

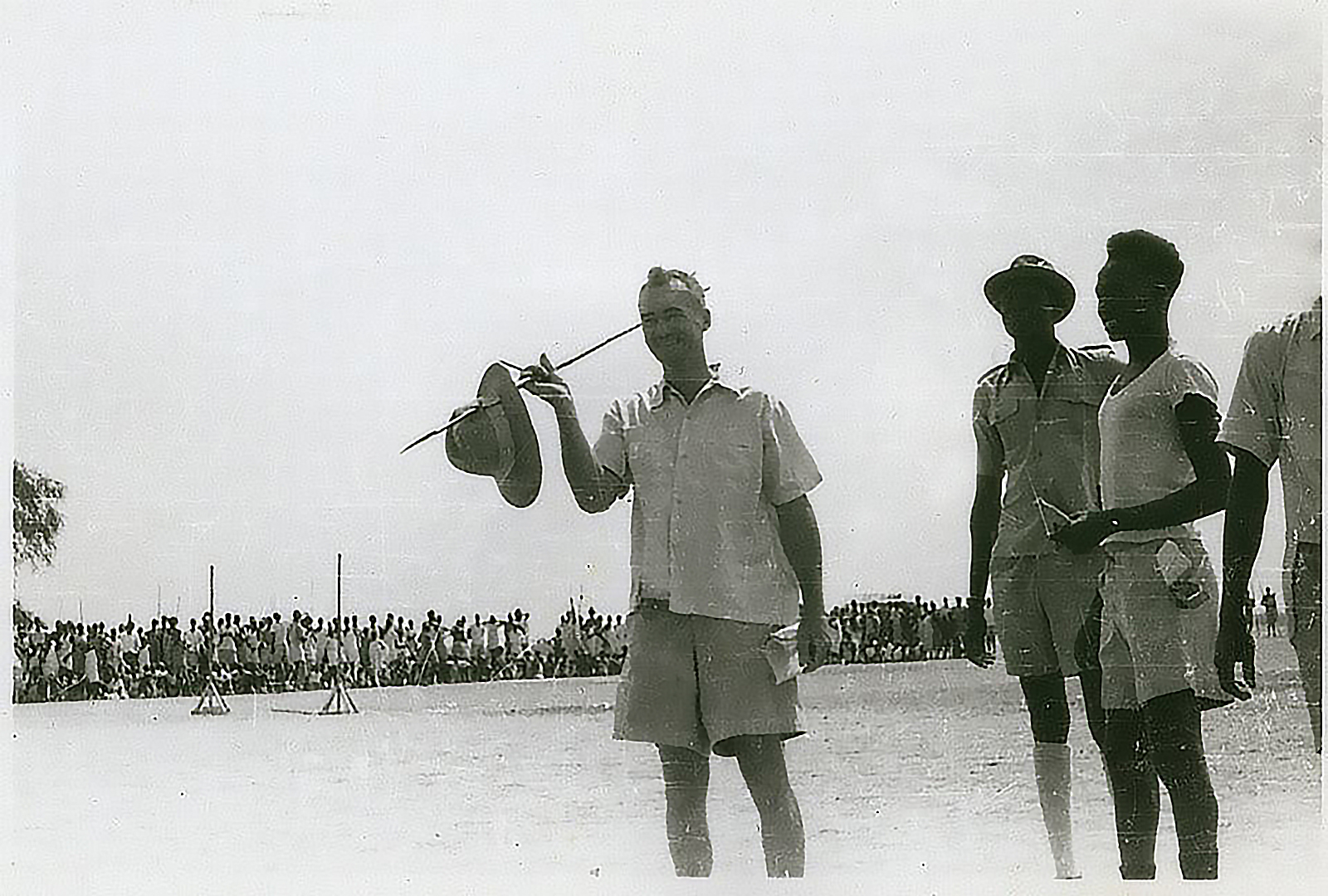

Now the Sudan Interior Mission (S. I. M. an interdenominational Mission) had accepted me at that time. The Field Director in Khartoum, Glen Cain, urged me to leave other training and come out. Alan had been pioneering in the south of Sudan all this time, opening up new stations. He was going into areas no white man had ever been before. He needed a partner, and the SIM needed couples to manage the stations he had developed.

But I knew I had to finish the Midwifery training. Mary Slessor was still influencing my life. I kept thinking about all babies who died at birth or because of treatment by a witchdoctor. I was sure the training was something I would need, and I was sure this was what God planned for me, so I continued with my training.

But before I finished my Midwifery - I’d done all the practical work - there was an opening at Mount Hermon Bible College. The Board decided that I could take my Boards at a later date. So, I started at the Bible College while still finishing the Obstetric degree. The lord gave me the strength, so I really did work hard.

I took the State exam for Midwifery and waited for the results to arrive. The day came when a thin envelope arrived, and I knew I had passed! If it had been a thick one, it would be the application to start over.

All the students at Mount Hermon Bible College were gathered together for morning prayer, the staff with us as, too. After prayer, the Phead Mistress had all the mail in her hands, and we had to wait for our letters.

As she began to give out the envelops, she said, “Now we have some news here.” She handed me that thin envelope. I had passed! I was filled with joy and so were the other students as they picked me up and carried me around the room.

“Now you can study some church history and comparative religions!” Said the Principle.

I had a wonderful time at the Bible College. And, just before the final term was ending, word came that the way had opened for me to go to Africa. But I couldn’t go alone. A couple was coming from America, the Forsbergs, and would pick me up in England on the way out.

I didn’t have time to prepare, as I left right from the doors of the Bible College. As I walked out the door, my school mates put their Bibles up in an arch and I walked under them.

The top staff from the College came to see me off, and my mother met me at the train station.

Now, I had enough money for my fare to Port Sudan, but I did not have enough to get from there to Khartoum, as I’d spent every penny on my education. I had a few extra dresses and underclothes, but nothing for equipment or much of anything else. However, I knew the time had come to go.

I also knew that Alan was currently 500 miles south of Khartoum and would not be able to meet me when I arrived.

I got onto the train, and as it started to move, the secretary of the S.I.M. came onto the platform and handed me an envelope through the window.

“Be careful with that!” He said. “It is a gift that just came in.” It was enough money to pay for the trip form Port Sudan to Khartoum.

The people I was going to travel with didn’t know that I had no money. They had spoken at my farewell, and people had given them money for supplies. (A nine-month supply of food was needed before going inland in Sudan.) I didn’t ask for any of it as I believed that God would provide, and He did. Before I left for the South, a missionary gave me forty pounds in Sudanese currency to buy the groceries I needed.

The woman who made the gift of the train fare from Port Sudan to Khartoum remained a true friend. Later, she sent me money when I needed it for a language study. When the time came that Alan and I were allowed to marry, she sent me money for my clothes. And later, before her death, she provided for our children to have extra education, like music lessons.

The first time I saw Alan Webb I was thirteen years old. I was helping Mary Hicks prepare her outfit for China, and as she and I left the Sunday evening service, she said, looking back over her shoulder, “There is young Alan Webb. He’s going to be a missionary, too!”

I looked back and saw a group of young men, one of whom was new to me. I saw him again the next Sunday morning teaching the boys class while I was teaching the little girl’s class. Afterwards Alan was introduced to me. He confessed “I found it difficult to teach because I was listening to your story!”

Alan started to teach a class of boys in the afternoon, and soon afterwards I was given a girl’s afternoon class to teach. We often met and compared notes. Then Alan started an evening meeting to show slides of Bible Stories to the children in the neighborhood. I took my three sisters and brother. It was well attended.

During the summer, we had open air services at the Church. Alan always gave the Gospel messages. We sang many old hymns and gave testimonies. Crowds gathered. Afterwards, Alan walked home with my two friends and me.

When Christmas season grew near, my friends and I had a party and the men’s Bible class came, too. A spider was noted on the wall behind me, and I was teased because I was so afraid of spiders. Alan came to my rescue and sat beside me.

When Spring came, my friends, Edie and Mable and I decided we would start studying the Bible one evening a week. We went into a field, as we had no meeting place. Winter came and Alan heard of our need for somewhere to meet. He found a home where we could meet. The teacher of the men’s Bible class offered to come and lead us, and our numbers grew.

For two years, I didn’t see much of Alan. I was busy in high school and with church activities. Alan was away at college.

About a year after I started nursing, I had an evening off, and some friends took me to hear some men who would be missionaries. They showed slides of their training and evangelical summer trips all over England and Wales. To my amazement, Alan was one of them!

After the meeting, he came to speak with the three of us, but I knew that meeting between us was special. He said he’d heard that I’d had a bath. I knew he meant my Baptism, and a started to explain, but he continued, telling me he had also been Baptized, for in Africa it was the common practice. He also expressed his pleasure to hear I was training to be a missionary nurse.

I would not see him for some time after that, but we both knew that a stronger link than just prayer partners had been made.

A long time later, I heard that Alan was ready to go to Africa with the African Inland Mission (A. I. M). In the final interview, for no reason anyone could give, the committee said that they had been sure that he was the man for the job, but they also felt a restraint that they could not explain. Alan was shattered.

Then the Sudan Interior Mission (S. I. M.) examined him thoroughly and accepted him for Ethiopia. Mussolini had invaded Ethiopia and Mission Red Cross units were being formed. It would take time to get a visa.

I was twenty-one. Alan gave me a wide margin Bible, and, on the front page, he drew diagrams of the names of God with references and their meanings.

Soon after that, I went on holiday to Wales. I nearly missed the coach because I was waiting for the mailman, hoping Alan just might send me a Birthday card, or even a letter. He did. Now I could send him an answer from Wales. To my surprise, I received a letter asking me to find accommodation for him for a special meeting. I pictured him bringing his Bible College friends for open air meetings in Wales, and for the first time, I felt shy. Surely, he would ask me to take part in the meeting, the only girl with all those older college men.

When the night coach arrived, only Alan disembarked.

“Are you alone?” I asked.

“Aren’t I enough?” He asked.

My shyness returned, but for different reasons.

I took him to my aunt’s home. She was almost blind. I prepared breakfast, knowing I could not cook because that wasn’t part of the nurse’s duties in the hospital. The breakfast was inedible, and the tea was weak.

He teased, calling it “Shamrock Tea” - only using three leaves.

We walked all day in the mountains, and in the evening, we prayed together with my aunt. Before he left for his room next door, he kissed my old Aunt. She teased him about kissing the wrong person, but Alan said he would only kiss the girl he meant to marry.

The second day we walked seven miles along wooded paths. It was early summer, and he quoted the Song of Solomon: “The time of the singing season of birds has come.”

Suddenly we were holding hands as we walked. We sat on a wooden log and ate our lunch. After Alan prayed, he asked me if I would go to Africa with him. I was not sure what he meant. I still had so much training to

finish.

“I’ll wait,” he said.

“Yes!” I knew my heart by now.

Immediately a lovely rainbow spanned the hills around us, and we felt God’s blessing upon us.

“Then we are engaged!” He said.

(Mum leaves out that Dad gave her an engagement ring with three Emeralds and two Diamonds. She asked if there was a significance. He replied, “yes there is. I want three girls and two boys in that order!” When she told this story she would smile sweetly and say that she obliged him and gave him three girls and two boys in that order!

Also, she doesn’t mention how Gran laughed when she told her she was going to marry Alan Webb. “Scared of spiders and caught by a Webb!” She teased)

But it would be a long wait and much deep concern during the Ethiopian war. His two companions were found, killed and mutilated. But there was no sign of Alan for nine months.

(Mum leaves out a lot here of the anguish and events during this time that she’s shared with me before this was written, including how she was pressured to give him up and marry a young wealth man who could give her everything the world had to offer. How staunchly she insisted Dad was alive and would return. And how, nine months later he walked out of the mountains and into Sudan.)

Finally, I finished all my training, and was on my way to Africa. I knew I had a year of language study before we could be married and also that we could not be on the same station.

After arriving in Khartoum and purchasing the eight months’ supply of food and medicines required, I started on the five-hundred-mile truck ride south to Uduk Country.

The Foresbergs with whom I’d traveled from London, and Glen Cain traveled with us. Alan had cleared a road to the station from the truck road and had built a permanent house in which Foresbergs would live. I was to go on to Doro and spend my first year with two ladies, even though it was not my language area.

The five-hundred-mile trek south in the truck for a London girl is quite a story in itself. Seeing inland Africa for the first time will never be forgotten.

After three nights of adventure, we started out for Uduk country - and Alan.

We saw a man striding down a tree-covered hill.

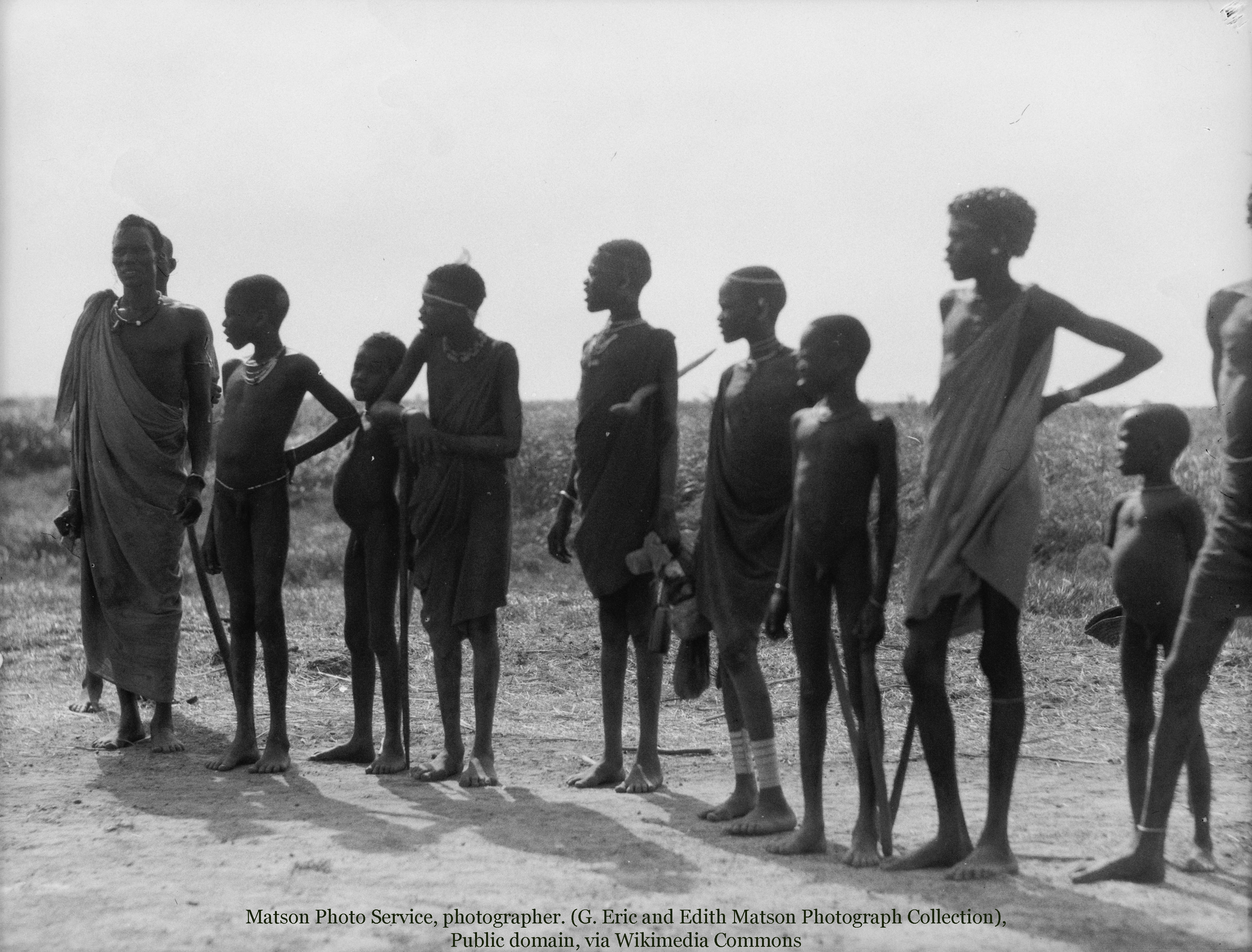

“There’s Alan!!” Glen Cain pointed. But it was a naked Uduk covered in red mud and all sorts of beads and bracelets, spears and a shield.

We came to the track Alan had cut to the house he’d built. When we arrived at the house, Alan had indeed come to meet us! A gathering of missionaries witnessed as he kissed me hard enough to ‘knock my toupee off’!

But we could not linger as the gathered missionaries waited to greet us. However, we were allowed to be alone for fifteen minutes that evening.

Alan’s health was low because he’d not had much to eat for so long. Tropical ulcers had developed on his legs, and I desperately wanted to nurse him back to health.

However, he was to go on the next day to a station on the White Nile in Dinka country although he had learned Uduk and had prepared a station for a married couple.

I was disappointed when I heard we weren’t to travel together as far as Doro as planned. Instead, I was to stay with the Foresbergs. This was not my language area, but the couple didn’t want to stay alone on a station as they had a small child.

Our farewell was witnessed by the other missionaries. We were not to meet again until my year of language study was up.

However, that year apart was not to be. The Field Director realized I should be moved to the Dinka area before the annual rains came and travel was almost impossible. The Foresbergs would be joined by another man.

It was hard to leave Enid with little Lee and Mal.

The next two months were exciting. The long trip through areas occupied by different tribes, the sight of Abaiyath, the station where Alan and I would live in Dinka country, and finally the River Nile, and the Trading Post where the Shilluk tribesmen came across the river to the Dinka’s side. There were large gatherings at the Post which was run by Arab merchants and where the flat-bottomed paddle steamers stopped.

Alan looked a lot better. He was boarding with the Lewis family, and eating fresh fruit brought in by the “Post Boat” - the steamers, because they brought the post (mail to Americans). And he was learning different languages, including Arabic from the Arab traders.

We were allowed to meet briefly in the presence of other missionaries, who were quite lenient with us.

I lived with Lois Briggs (who in later years retired to the same mobile home park in California as us). A New Zealander lived with us, too. We took turns cooking, so we had a variety of diets. Lois helped me learn the Dinka language.

The church there was well established, however I was a bit shaken to hear the tune to “Clementine” as we walked to the Church the first Sunday. But the Dinka words translated “Come to Jesus”.

(The missionaries weren’t all that musical and it was easier to use simple tunes they knew to the Dinka words, rather than the classical Church music of the time. MB)

Alan would bring me bouquets of Oleanders which made the Dinka curious enough to ask why. Soon afterwards, we saw one of the language teachers, a Dinka, clothed in a knotted cloth over one shoulder, trying to hide a bunch of Oleander blooms. He was going courting!

Soon after I arrived at Melut, a runner came with an urgent request that I return to Chali as Lee Foresburg, now two years old, was very ill with dysentery. The roads were officially closed as it was the rainy season, but the received permission from the District Commissioner to go by an Arab Trader’s truck with an Arab driver. We were to return as soon as possible.

Earl Lewis, an older missionary, and I boarded the truck with bed rolls. He took a powerful rifle so that we might obtain food and leave it at each station as we passed.

When we arrived at Chali, where Enid and Mal anxiously awaited us, I checked on Lee at once. We stayed through a second day only, knowing that heavy rain was eminent, and that we would be unable to return to Melut.

Fortunately, Lee’s health picked up quickly, as children often do. The Foresburgs were comforted. I gave Enid medicines and instructions about food and fluids. As they wrote in their book later, Enid was so happy to see me again. She had not had a woman’s company for some time.

On the way back, Earl Lewis shot several good meat animals which, again, we dropped off at the stations on the way. We hoped to get back to Melut by nightfall, or at least to one of the mission stations before the rains began. But rain began to fall as we passed through a rare, forested area in a low place in that vast, flat land. There were thorn trees there because of the extra moisture. The road was boggy, and the truck plowed into the mud and was quickly hopelessly stuck.

The Arab driver found some Dinkas who lived in a village not far from the road. They used their united effort, but the truck still stuck fast in the mud.

We had to settle for the night. Earl set up my cam cot in the back of the truck with dead animals all around. The driver took the comfortable seat in the cab. Earl set up his cot at the side of the truck, on the ground.

Darkness fell almost at once. Not a glimmer of light as clouds hid the moon and stars. We had prayer and sang a few hymns, then tried to sleep.

Very soon, Hyenas caught the scent of the dead animals.

“We’re stuck in the mud, cold, hungry, and the Hyenas com to scorn!” said Earl.

“I don’t mind their mirth, as long as they laugh from afar.” I replied. I was still very new to Africa, so when the lion began to roar, that was more serious.

“They will get me first, and will not come for you, unless they want dessert!” Earl chuckled, then began to quote Scripture. “I will both lay me down in peace and sleep. For Thou, O Lord makest me to dwell in safety.”

I answered, “Thou shalt not be afraid for the terror by night, nor for the arrow that flyeth at noon. The Lord thy God is with thee withersoever thou goest.” I also remember that Alan and I had claimed Joshua 1:8-9 for ourselves when we were engaged.

(Joshua 1:8-9. 8 This book of the law shall not depart out of thy mouth; but thou shalt meditate therein day and night, that thou mayest observe to do according to all that is written therein: for then thou shalt

make thy way prosperous, and then thou shalt have good success. 9 Have not I commanded thee? Be strong and of a good courage; be not afraid, neither be thou dismayed: for the LORD thy God is with thee whithersoever thou goest.)

So, we slept throughout the night, exhausted, but resting in the Lord.

In the first glimmer of light, the villagers came, glad for meat in exchange for the labor. They cut down branches from the thorn trees, stripping of the large thorns. Scorpions had come up out of the cracks in the

ground caused by the dry season and had taken refuge in the trees. Several of the men were stung by scorpions. I gave them Aspirin, which helped with the discomfort. They were not used to feeling relief like that.

At last, we were on our way again!

How good it was to be back in Melut! No one protested when Alan hugged me in welcome and relief.

After a few months, Alan’s work at Melut was finished. He was sent inland to supervise the building of a house, which would be our first home at Abaiyath, which is thirty-five miles from Melut in the Dinka country. John and Peggy Phillips were already living there, learning the Dinka language.

Alan was permitted to visit me once a month. As it was the rainy season, the road was closed being wet with mud. So, he walked in, stayed overnight with the Lewis family, and went back the next morning. On one of these occasions, he started at dawn, and I saw him off. I sat by the river praying as I watched the sun rise. My foot was at the water’s edge and a crocodile made a rush, just missing my foot! I ran up the bank and the crocodile followed me. I had no idea that crocodiles could run so fast! Shaken, I made it to Lois and Daisy’s house.

A few days later, word came that Alan was very ill. There were no doctors in the area, and a nurse was needed. He had Blackwater fever from which few recovered. I looked up the details in tropical medicine books, but I would not be allowed to nurse him as we were engaged. Lois was the official nurse at the Melut Station, but she refused to go because she was involved in a language study. It was a kindness to me, because that meant I would go in her place.

I had nothing to help him except my nursing skill and willing him to live. We had no I.V. equipment, so I could only give fluids slowly per rectum. I had only one injection to stimulate his heart in a dire emergency. That emergency came, and I gave him the shot.

Later he told us that he saw a lighted doorway. He could enter or return to his work and to me. His work was not finished, and he came back to me.

Gradually, slowly, he crawled back to health.

The road finally dried sufficiently for us to get permission from the government for a truck to take Alan to board the river steamer. He would go the five hundred miles to Khartoum by steamer. There he would rest and recover. I was not allowed to go with him.

I had hoped to follow soon afterwards so that we could be married. However, the Phillips, the couple on the station, went to Kenya for a month and I had to stay at Abaiyath with Daisy McMillan to hold down the station. when the Phillips were due home, we had word that they would stay longer in Kenya. I was quite ill with dysentery. The Government Doctor went through our station without stopping, but a houseboy ran some 15 miles to a rest house where the Doctor spent the night. He came back at once and said, “You must get the next steamer to Khartoum.”

I told him I was going to be married there soon. He said, “The best possible treatment! Doctor’s orders! On the next steamer!”

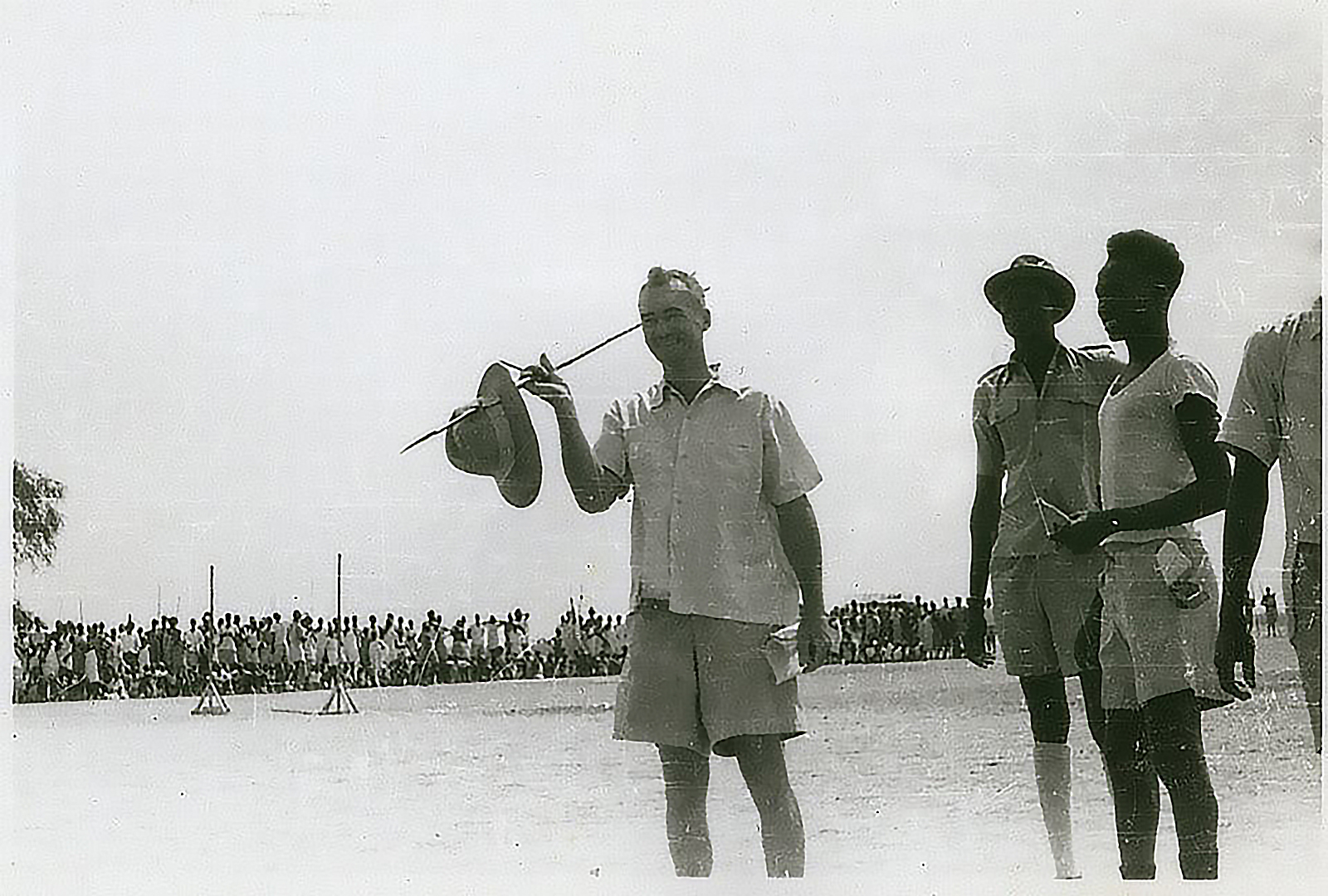

So, I arrived in Khartoum a week later. Alan was pale and very thin, but he had everything arranged for our wedding. We were married at the Mission Headquarters of the Sudan Interior Mission in Khartoum, February 8, 1940. After a wedding breakfast with missionaries and Bible Society, we had to be married again by the British Governor of Khartoum, which made it legal.

For our honeymoon, we went across the desert to a British government rest house which was in an Egyptian settlement for the maintenance of the Jebel Aulia (Aw-lee-a) dam and bridge, which crossed the river and was three miles long. The bridge was an excellent walking place. We passed camels laden with mostly firewood, donkeys and Arabs, and saw all kinds of interesting sights, including the rushing waters when the dam was opened for a little while each day.

After our marriage, we prepared to return to the South to live at Abaiyath. The house was not finished, and our things were still in crates, but we moved into the finished part, one bedroom and a sleep out with a cement floor. There was loose soil on the new floors and new timbers were hiding places for scorpions. When the first rains came, the scorpions all came out. Our houseboy was stung, and we could not move without watching where we stepped or put our hands. We put the mosquito nets down and tucked them well in around the beds to protect us from falling scorpions. we killed many one evening and longed for morning.

Several months later, as I came in through the back door, I trod on the head of a green viper which whipped around my leg. Fortunately, I was wise enough to stay still with his head under my foot.

I was expecting Jessie, and I was very sick. Our diet was meager indeed. One day, Alan caught a band of Dinka cow herders driving their cattle past our house. Alan went out and asked to buy milk from them. They said, “Women do not drink milk, or the cows go dry. We will sell some for you to drink.”

Alan made cocoa for me because I was ill. Unfortunately, he put in salt instead of sugar as the containers looked alike. He proudly presented it to me, but I could not possibly drink it. He almost wept! Later we would laugh about the cocoa made with salt, but not then.

There were no Christians, as yet at Abaiyath. The houseboy, gardener and language teacher sang Dinka hymns with us. I began to read the Epistle to the Romans. It had been translated into another dialect of the Dinka language. I wanted to read Romans to them because, although that was strong meat for a firs lesson, it was all that we had of the Bible. They stopped me and said, “God knows the heart of the Dinka.”

The ground was broken. They knew they were sinners and separated from Nyalic, the Great Spirit Above.

I also had a children’s time for singing Dinka hymns. I went and sat with the children in the village. It was a good language study as the children laughed at every wrong pronunciation.

One of the young men named Loeth, came to hear the children sing and also to my Romans class, was taken very ill. He refused witch doctor medicine - he refused to have a cow sacrificed. He said he believed in the Lam of God. I did not know about his illness until it was too late. Lueth died, but he was the first Dinka in that vast area to believe in Jesus.

As I worked with the Dinka language, I had one sheet, a translation of John 4. I learned to say, “A woman went to the well to draw water,” (there are male and female differences in the language.) But, although I tried again and again, they would not accept it.

Finally, they told me, “A man would not draw water. That’s woman’s work!” I was using the word for man, not woman!

The time came for us to go to Khartoum, five hundred miles north by steamer, for the birth of our first child, Jessie. While we waited in Khartoum, Alan was appointed Army Scripture Reader, and the Mission Headquarters became the home for the soldiers and airman’s Christian Association. Alan wore an army uniform and visited the barracks during the day.

I took Arabic lessons and was always available to visit with the airmen and soldiers. We had supper for any who came to eat, followed by a service. We had games, like table tennis, and always time for quiet talks.

One airman accepted Christ as his savior. On his next mission he was killed. This made a difference in attendance and earnest soul searching for truth and commitment to Jesus Christ.

The first of January came. I knew the baby would soon be born. The Scottish doctor had told me any day but New Year’s Day. So, Jessie waited until the second of January 1941. What joy for us! When we took her back to headquarters, she was the soldier’s darling. Many of the lads had babies at home they had not yet seen.

Alan had not had a furlough since he began his work in Africa. We had to serve ten years between us to earn one year at home in England. Because of the war, there was no passage home, so it was decided that we would take a year in Kenya in lieu of furlough. Alan’s illness had not reoccurred, so we felt it was safe to return to the area. We planned to visit mission stations and observe the educational work.

That year is a story in itself. We became better acquainted with the fine work the Presbyterians were doing in education (this later plays a huge part in Mum’s story MB).

When we returned from Kenya, Alan was convinced that we should begin schools in earnest in South Sudan. We found that there was some tension amongst the SIM missionaries at that time. Dr. Lambie, the great pioneer, was ageing. It was felt that he should retire. Some potential leaders felt that all efforts should be made to start the church in each tribe and start schools only when there were children of believers. That would take years. The church needed educated leaders now.

Dr. Lambie sent Alan to Egypt, recommending him to the Presbyterian Mission as a teacher at Asyut College He also suggested that I would be a good nurse at the mission hospital. It was agreed that I should follow him,

but the Battle of El Alamein made it necessary to send all the women and children back to the U.S.A. The single women were to take refuge in the Sudan.

Unable to go to Egypt, we went to Banjang. There were new prophylactic medicines against Malaria that would protect Alan. We would have gladly stayed there except for the restrictions of the mission leaders concerning

schools and treatment of the sick.

Certainly, evangelism was our key purpose, but to heal the sick and to train future church leaders through education was also very important to us. The time for missionaries in Sudan might be limited. We needed to build a church which would continue after the missionaries were gone.

Today (at the time this was written in 1987) that mission has leaders sufficiently trained to study in Lebanon, Egypt and the U.S.A.

Alan started a school for five boys, who much later we met again at Khartoum University. We were reproved.

Word came that our passage was booked to Asyut, Egypt. But we had no way to leave Bengjang - no steamer ever stopped there. And the rains had started, so the roads were closed. The SIM would not help us because they did not want us to leave Banjang.

Word finally came from Malakal - the largest town in the province - that in two days a steamer would stop at Banjang for a trader. The arrival time would be around 2 a.m. we packed in a hurry and parked on the riverbank with baby Jessie under a mosquito net. It was a night never to be forgotten with the crocs and hippos all around us and mosquitoes buzzing in our eyes and ears.

The steamer arrived and we hurriedly got our goods and ourselves aboard. We were finally bound for Khartoum and on to Egypt.

In Khartoum, we once more found tension in the mission, this time because we were joining the Presbyterian Mission in Egypt. So, we stayed at the Bible Society with an old friend, Mr. Hamilton. His real name was Prince Albert, and he was from Jamaica. (A favorite “Uncle” of ours as children. All missionaries and friends were called Aunt or Uncle. MB)

Jessie was less than two years old when we boarded the train for Egypt.

What a welcome we received in Asyut! We lived at the hospital where I would work, helping to train Egyptian and two precious Sudanese nurses. There were also American and Egyptian trained nurses.

Alan bicycled several miles to Asyut College where he taught English, Bible and football (Rugby or Soccer). He arranged soccer matches between the college and the army.

Once again, we were involved with the soldiers and airmen in a Christian Association. The hospital had a guest house and entertained the service men there.

It was then that our second child, David, began to make his presence felt. When it became obvious that a baby was on the way, it was unseemly for me to work in the men’s ward in Egypt. (I was working at the leprosy clinic). So, I gave lectures in psychology, physiology, anatomy, general nursing and hygiene. I loved those nurses.

David was born on May 14, 1944, weighing 11 lbs., in Asyut (Hospital and Dr. McClanahan used the experience as a practical lesson for my own students! How those nurses loved baby David!

Now it was decided that I should lecture at the Presley Memorial Institute, a large Presbyterian girl’s school. I took the children with me, and gave lectures on childcare, using David and Jessie as examples.

We moved to the college where better accommodation was available for the family, and Alan could be available at night for college needs. He had a very large Bible class.

We traveled to other institutes by horse-drawn carriages, which the children loved. They were the only mission children as all the other families had returned to America during the war.

During the three months summer breaks, the children and I went to Alexandria - to the Presbyterian camp there. Alan stayed in Cairo and graded government exam papers.

During one of these summer breaks, Jessie became very ill with Typhoid Fever. We had nearly lost her in Kenya with gastroenteritis and now, again. We prayed for a miracle. Alan could not come to Alexandria, so I took her to the Tanta Hospital. There her life hung in the balance.

But God had plans for her, and she crawled back, with the help of the Mission doctor, Dr. Moore and his daughter who was a nurse there.

It was a difficult time for me. I was still nursing David who was seven months old. And needing to care for Jessie who seemed to be dying. When Alan was finally able to come back to us, Jessie was still so weak she couldn’t raise her head to greet him. But God spared her for us, and our family was reunited.

We went back to Asyut. Now I was busy with my children and with Church activities. Alan was joined by two other short-term missionaries to help with the workload at the college. The younger families still remained in the USA, so ours were still the only children. Jessie and David were showered with love. And Nellie was born towards the end of our three years stay in Egypt, making her appearance on March 3, 1947. Jessie and David pulled her around the grounds in a little red wagon.

On one outing, we visited the cow barns. Mr. McFeeter’s project for improving the stock for the Egyptians. A prize Jersey bull was tethered in the stall. No one could handle him, although he was very valuable for breeding. Unseen by us, Jessie, who was still very thin, slipped through the bars and went up to bet the bull. Fortunately for us - and probably her - we couldn’t get in to rescue her. The bull accepted her where he would not have accepted us if we’d tried.

Our three years in Egypt were finished and we had to make a difficult choice. The college asked Alan to stay as a full-time missionary.

Don McClure came to visit. He told us that the Presbyterians planned to open a teacher training center in Sudan. The best student from each of the five tribes we served was to bring his students for a practicing school.

In the meantime, we had almost decided to join the British mission in Tanganyika, where the hospital and the school were on a mountain, mosquito free. The was also a school for the mission children. They promised to prepare Alan for ordination, which he very much wanted. Choosing Tanganyika seemed common sense for the children and for Alan’s health, as well as the fulfillment of his desire to be ordained.

While in Egypt we were very busy and happy, but the Sudan was our first love. After praying long and earnestly, we decided to pick the hardest: if God did not approve, He would close the door.

To prepare for the Sudan, the British government offered Alan a year at London University to study colonial education, especially teacher training methods. The war with Germany was over, but there were still submarines that had not surrendered. Shipping to England was nil and only key personnel were allowed passage.

We were serving as short-term missionaries for the Presbyterian Board of Foreign Missions. When we decided for the Sudan, Don McClure asked the Board to take us on as full-time missionaries. The British Government paid for our passage to and from England and the college fees, but the Board paid our support from the time we agreed to go to the Sudan and start the Teacher Training Center.

Twelve days later we were booked as key personnel by the British Government on the only steamer leaving Alexandria for England.

The crossing is a story in itself.

The boat was filled to capacity: women and children sharing the cabins while the men bunked with the soldiers. (I wish she had told us more about the crossing, because I know they encountered a U-boat. Jessie had told talked about it in her memoirs, but they were lost in the California Campfire along with all Dad’s slides – a whole oil drum full of slides of his work in Sudan.)

The food was good, and when we landed, we were given food to take home and share our first meal in England with relatives.

We were happy to see our relatives and friends. For Alan it had been twelve years. He had served in Ethiopia, the Sudan and Egypt. His mother had died, his father was weak and crippled.

Jessie told my Bible college president that her goal was to go to Bible college and teach Bible, as Mommy did. She kept that dream and has remained true.

David and Nellie were thrilled with all they saw and everyone they met.

Accommodation was very scarce because of the bomb damage. We stayed in London with my mother and sisters, Doreen and Joan. It was a tight squeeze! After three months, we found accommodation in a country town, where Jessie could go to school. Alan took the daily train into London to the University.

At last, Alan passed the exams with flying colors, and we were ready to return to the Sudan.

Before Alan had started his missionary training, he had studied to be an architect. He left that study to start theological training, but his early studies were very helpful in our next work. While studying Colonial Education at London University, he drew blueprints for the Obel Teacher Training Center. He planned in such a way that everything could be reproduced by the trained teachers when they started their own village schools.

The Board sent out an American builder, Ted Pollock, plus Rod McLaughlin, to build the school to Alan’s plans. They also sent out a short-term missionary, Talmage (Tal) Wilson to assist Alan. All of these men came back later as full-term missionaries, bringing their wives with them. They became part of our rich fellowship.

The Training Center was to have two missionary homes with a site for a third, if needed. There would be houses where teacher trainees from each tribe might live, houses for married teachers and circle houses for the boys from each tribe. Each school would have a kitchen, a clinic, a workshop, and the all-important cattle barns as these people were cattlemen. The cattle would provide meat and milk for the school. Later, we bought our own cows and a bull for breeding better stock for the school.

Every adult male took the name of his best bull. They named Alan after his best bull, too, for his bull was the most powerful of them all. This meant real acceptance amongst the men.

While the school was being built, Alan and I lived at Atar where a British government secondary school already existed. Atar was some fifty miles upriver from Obel. We were allotted a house there which was intended for a Presbyterian pastor and family. He was to be the Chaplain of the school. We were allowed to start the Teacher Training Center, and to use the classrooms and housing for trainees and for the boys participating in school that were already built.

Later, Lowrie Anderson filled the Chaplaincy at the government school. He and his wife, Margaret occupied a smaller house, letting us stay where we were. We had wonderful fellowship with them, and with the British Principal and the teachers.

The second year began. The school and student housing were complete, but the missionary houses were not even started. Upon inspection, the Government said we could not possibly be ready to open that year. But we were determined to get the school under way, beginning the training program so that the Spiritual side of the work might begin. We said we would live int the workshop, and Tal Wilson could stay at Dolieb Hill, three miles away, riding a bicycle to and from Obel. When the rains started and the roads were closed, Tal slept in the clinic.

Our thatched roof, one room building was large enough for five beds with mosquito nets. During the day, we put the beds outside and set up tables and chairs inside, and in the evening – in the rainy season – reversed the order. In the dry season we just slept outside under the mosquito netting. It was a rather dangerous thing to do as this was lion country, and mosquito nets weren’t much deterrent to lions! But we trusted God.

Jessie, David and Nellie were active children, and we were ever watchful for snakes. We had a dog who actively guarded the children out in the yard. (This might have been Pal, an Alsatian – very similar to a German Shepherd, but from Alsace-Lorraine, a small country between France and Germany. I remember Pal, but I had not been born yet, so this may have been another dog. MB)

The time had come to open the school and we began the day at sunrise, around 6 a.m. with the whole school gathering for prayer. The time didn’t vary much all year because we were so close to the Equator.

After that, I opened the clinic for care, and again in the evening. I was immediately inundated with undernourished little boys with eye disease, tropical ulcers on their legs and feet, Malaria and Dysentery. There were also many snake bites and scorpion stings as well.

Alan asked me to make a flag for the school. We chose a green background for the prairie lands with a large yellow village hut in its center. The flag drew us all together. We became one in the Spirit, and one in the Lord, which was much needed amongst these warring tribes.

(I am inserting this here to help the reader understand Mum’s next part of her story. MB)

None of the tribes’ languages had ever been written when Alan first arrived in Sudan. To communicate with the men and learn the language and create a phonetic alphabet, he would draw a picture of an animal or object on a portable blackboard and write the English word. Then the men would tell him what they called that animal or object, and he would write it phonetically. He did this with many languages – my understanding is seven – and many years later when Wycliffe came out to begin translating the Bible, they used his work as a starting point. Alan used this technique in the school, having his teachers prepare a blackboard the night before.

The school assembled at the base of the flag for morning and evening prayer and singing, at least during the dry season. Morning prayers were followed by marching drills as each teacher lead the boys of his tribe. Then the whole school body marched together to the classrooms.

(The boys sang as they marched. I can remember hearing them. The leader would sing something, and the boys would respond – much like one might hear in our own army training here.)

The teachers would present their blackboards to their students with a new picture and a few new words or sentences, with yesterday’s words in a different color. The students quickly learned to read simple sentences based on life around them.

At 9 a.m. a drum was thumped to announce breakfast.

Planning food for such a crowd was work indeed. The Post Boat (paddle steamer) stopped over a mile away on the Nile River. We were on a tributary called the Sobat. It nearly always came at 2 a.m. When Alan heard the whistle, he roused the teachers and headed to the landing to unload and carry sacks of grain back to the school.

I followed the same school pattern at home: my children had some education, some exercise, some prayer, some Bible study. Our next baby was on the way during the first year, but I kept very well and very active.

It was time for Jessie to go to school (This would have been possibly 1947. Jessie would have been seven or eight years old). We showed her pictures of planes with their beautiful interiors and smiling hostesses. When the time came, we took Jessie into Malakal, to board one of the few planes that flew to Ethiopia. When we went out to the plane on the tarmac, we found the pilots and assistants were all American, but the plane wasn’t at all like the pictures we’d seen. Bucket seats lined up against the sides, the center left open for cargo. The cargo on this trip was monkey skins that smelled horribly. Jessie was taken aback – and so were we! The Pilot told us that as soon as they took off, he would give Jessie flying lessons, sitting up with him in the cockpit. She would see all the animals and scenery. Jessie recalls that trip as being a lot of fun as she was allowed to fly the plane.

Dr. Gershner, of Pittsburgh Seminary and his wife were visiting at the time and came to see Jessie off with us. Mrs. Gershner said, “I never before understood the cost of being a missionary.”

We missed her so very much! Her letters came regularly and were full of stories of her new friends and the beautiful country around Addis Ababa in Ethiopia.

At last, our house was finished, and the second house started. Tal Wilson now lived in the clinic because the roads were too difficult during the rains, so I had the clinic on my back veranda. There were many snake bites as the snakes were very active at the beginning of the rains. Many fishermen and villagers came for treatment for snake bits. The young man who was a general help around the house – called a House Boy – would tell them, “You will be all right now, NYAYIK will save you!” Many switched their faith from the witch doctors to Nyayik, and I sought to switch their faith from me to NYALIK, the Great Spirit in the Above, and to God, Himself.

My Shilluk was improving, and I started a class for the teachers’ wives. Some were Shilluk or Dinka and I could converse with them fairly well, and the Nuers and Anuaks were able to talk with the Shilluks, so our classes sounded like the Tower of Babel! I was also able to teach them how to sew and knit. Churches in America sent supplies equipment for these endeavors.

I needed to be near a doctor as my delivery date was coming up. We were told to move to Dolieb Hill for a few weeks as the rains were coming, and the roads would be closed. We moved into an old mission house with a thatched roof that was close to Dr. Al Roode and his family. Nurse Mary Ewing also lived at Dolieb Hill. I needed the rest and the fellowship with other missionaries.

Each day Alan went to Obel by a dingy with an outboard motor. He did the marking and lesson planning at home with us in the afternoon and late evening. Tal Wilson helped the porter at Obel at night and took care of the emergency clinic work. Some of the teacher trainees were very helpful at this time, being good company for Tal and being strong influences in the school. Some had assisted me in the clinic, and Alan had Red Cross training from his time in Ethiopia. So the health of the school was taken care of.

While waiting for the birth of our child, I delivered Shilluk twins who were named after Alan and myself (remember, twins were normally thrown out on the heap as they were thought to be evil. This was a great success for Mum!). The need for a midwife at Dolieb Hill was obvious. The women’s Board arranged for Mary Ewing to return to Kentucky for the training.

(I added this section as the stories Mum told us were much more involved than in her original memoirs.)

Jessie was still home for the summer holidays. Now, we had few books for the children to read, other than the Bible. Jessie enthusiastically searched through the Bible trying to choose a name for this baby. Zaccariah, Melchizedek, Nebuchadnezzar, Zerubbabel –

“Jessie,” I cried. “Why on earth would you want to call your baby brother Zerubbabel?”

“So I could call him Rubber Ball for short!” She responded, matter-of-factly.

“Gracious me! I must find something else to read to you than the Bible!” I muttered with images of a baby bouncing like a rubber ball. I found a book about Robin Hood, and Jessie was soon enthralled and insisted this baby would be named Robin. Amused, Alan asked what if it was a girl?

“Well, she will be called Marian, of course!” Jessie answered as if that was just so logical anyone should have known it.

(Returning to Mum’s memoires)

There was great excitement the night Robin was born. I was attended by Dr. Al Roode and Mary Ewing. Alan was able to be with me in the tiny, thatched-roofed house. The walls did not reach the ceiling, and the children were in bed in the only other room. They were very excited, and we chatted with them as we waited. Robin arrived, a healthy ten pounds, five ounces, unaware that he could have been named Melchizedek or Zerubbabel.

Within a few days, I took the children swimming in the part of the river which had been enclosed by bamboo stakes for the station and school at Dolieb Hill. It was too soon after Robin’s birth for me, but the children were so wanting to swim, and the doctor agreed it wouldn’t hurt. As a result, I was very ill with strep infection for a while. But thanks to antibiotics, I soon picked up again.

One morning the air felt very chilly as a strong wind from the north blew in, signaling the star of the dry season. I was delighted with the cooler weather, but the builders working on the station were miserable. They did not like the cold at all.

With a burst of energy and excitement, I put Robin in a wheelchair, and Jessie, David, Nellie and I started off for a walk, taking turns pushing the chair on the rough road. We visited the large Shilluk village between Dolieb Hill and Obel, then continued toward Obel. I knew Alan’s school would be finished at two o’clock, and that he had the boat there for the return trip. Tal Wilson had given the children some snacks to tide them over on our walk, and it was a good thing, as I had not expected to go so far, and had not brought anything for lunch. I had certainly re-toned my muscles and I felt wonderful!

The Association of Presbyterian Missionaries in the South Sudan met once a year. While we were at Dolieb Hill, the yearly meeting was held there. Missionaries from each station came for a week’s conference on Mission Policy, reports on work. Problems, plans for upcoming events, furloughs, in-country leaves, as well as worship and fellowship together. I was asked to lead early morning prayers, and I still well remember reading and commenting on Luke 10 – the record of Jesus sending out seventy other disciples, two by two.

First, they were to PRAY that the “Lord of the Harvest” that He would send forth more laborers - and, oh, how we needed more laborers in the harvest fields of the Sudan!

Then they were to GO. But we don’t just go where we think it’s best. “I send you as lambs among wolves,” Jesus said. There would be wolves, but the Great Shepherd was sending them, and would protect them. They were not to worry about supplies with them, God would supply their needs.

Their greeting was to be “PEACE”, and they were to heal the sick and preach the gospel. The responsibility was with the hearer to believe and accept or reject the message. If accepting it, they were to be faithful to their calling.

On Sunday I was asked to give the Bible Study for the women missionaries. During the worship service, Robin was baptized. Jessie asked if she could join the Church (she would have been eight or nine years old). She insisted that she join the Shilluk congregation, with the Shilluk Pastor asking her all the same questions that the Shilluks must answer in order to understand that the Church is one, and all must come the same way, through faith in Jesus Christ. The Association members agreed to Jessie’s wishes.

The Shilluk Pastor asked Jessie all the questions before a congregation of Shilluk and missionaries. How I thanked God for revealing Himself to her, and for her eager acceptance of all that we had taught her of the Word.

Dr. Heasty, father of Dr. Alfred Heasty, had been at Dolieb Hill for many years and had many good stories to tell. His favorite was of the Shilluks who brought milk to sell at the door. The milk needed to be strained and boiled for safety. Over time the milk got thinner and thinner. Dr. Heasty challenged the men about adding water to the milk, but of course, they denied it. One day as he was straining the milk, a small fish fell into the strainer. He presented this to the men who brought the milk from their camp across the river. Unabashed, the Shilluks told him that the cows drank from the river, so one should expect a fish in the milk from time to time.

(This story was told many times over having happened in different places and to different people. I originally heard that it happened in Khartoum where the milk was brought in on the back of a donkey by an old Arab. It was Mum who discovered the fish in the milk, and the man's spoke with the fames Arab shrug was, “So the cow took a drink just before I milked it!”)

When we returned to Obel after Association, our house was ready for us. Although not yet complete. We had a very large veranda so that we could have the teacher trainees in for singing every Wednesday evening, along with the staff. How we loved those evenings! We had as many as forty singing their way through the GOLDEN BELLS Hymnal (I still have a copy of it. MB) Our children learned many hymns and often they took part in the group prayer, as well.

From time to time, I had a tea party for the trainees and staff on the veranda. The Shilluks and Dinkas loved sugar in their tea. When I put in my order for eight months supplies, I had to remember to include another sack of sugar!

It was time to start teaching my own children. David and Nellie learned to read and write at a very early age. Math was important and much of that was learned through games (Skipping rope to the times tables. “2 times 1 is 2, 2 times 2 is 4, 2 is 3 is 6 – how well I remember! (MB) They would enter third grade when they went away to school, but I felt the basics were to important to wait until that time.

Jessies letters from boarding school raised a problem. Her spelling was different for many words, and I was amazed at her fancy capital letters. I hesitated to correct Jessie until I was able to talk to Margie Anderson on her visit. She was much older than Jessie. I asked her to show me how she made her capital letters. They were exactly like the ones in Jessies letters – drawn according to American standards, not English – as was the spelling!

Through the children’s schooling, political problems arose, making it necessary to keep them at home, and I continued to teach them and Jessie, too. I had to learn about American History, Geography, vernacular and spelling along with them! I also still had to run the clinic, so the children understood that, should I be called away to deliver a baby or another emergency such as a snake bite, they were to complete their assignments before play.

We were a very happy family. Settled into our new home, we planned a garden. We were situated on an ancient village site. The soil was largely ash from the old village fires. He surface was dray and a little elevated, so the heavy rains ran off into the river. While Alan was involved in the school, the children and I spent time each day digging long, deep trenches. Then I paid some schoolboys to carry river soil fill the ditches. That soil was rich, having come from Ethiopia via the Sobat River.

Soon we had tomatoes growing. Although it took years to get other vegetables to grow. We taught the teachers and the boys that tomatoes were very food for them and we saved seeds for them to take back to their native villages.

Flowers grew well, and we soon had a wonderful show of zinnias, marigolds and flowering shrubs of Lantana and Oleander, and many colors of Cana Lillies. Villagers asked us which part of these plants could be eaten. When we told them none, they were amazed that we grew them just because they were pretty. We warned them not to eat the flowers, especially the Oleanders, as they were poisonous.

We also planted peanuts. These the natives could start in the villages and benefit from the crop, especially when locust swarms took all of their regular crops. Soon a school garden was started with tomatoes, peanuts and other edible plants.

Later, we traveled to the Nuba Mountains, Kenya and Ethiopia for in-country leaves. We brought back cuttings and started all kinds of bushes and trees. Alas, they are all burned up now, along with all the houses and the school.

Tal Wilson’s three years as a short-term missionary were finished, and he went back to America to marry his fiancée, who was studying medicine. They returned later as full-time missionaries.

Wilma Kats came from Akobo for the first part of the school year at Obel. She was one of the Dutch Reformed missionaries with whom the Presbyterians had a partnership in the Sudan. Her stay of five months was delightful. Where Tal had been an “uncle” to the children, they now had an “aunt”. Although Wilma worked with Alan in the schools, she became a part of the family. I enjoyed having a woman friend that I could invite for dinner and conversations. Too soon, she had to return to her work in Don McClure’s Anuak Project.

Marian Farquar came for the rest of the school year. Everyone was “Honey” to Marian. She was a warm and enthusiastic person, and the children loved her, too. These two ladies were able to visit nearby Dolieb Hill, where several other women were working.

The school year was over, the trucks came to take the different tribes back to their native villages. Some students went by the Post boat – a flat-bottomed paddle steamer – along the river to other stations close to their home villages. They would all return in three months.

Many of the boys had accepted Christ and been baptized in the River Sobat. Many more would follow in witness and baptism.

(The boys and the families in the nearby villages always sang whatever they did. When they marched to the soccer field, they sang, when the women pounded grain to make bread, they sang, when they were thatching a roof or building the mud walls of a roundhouse, they sang.)

Jessie remembers as those trucks were rolling out of the school yard, a mighty hymn rang out instead of the native songs they had sung as they arrived. Obel had become the place of song – and Obel was sharing its message of salvation through Jesus Christ to vas areas of South Sudan.

With the ending of the school year, we were due for an in-country leave. We had been invited to visit the Nuba Mountains on the west side of Sudan. (The Nuba Mountains are west and north of the Nile River and its tributaries, but it is much more north than west.) We had traveled with a couple from there when we came back from Kenya previously. We went by Nile Steamer (The Post boat) south (actually, the Nile heads west from the mouth of the River Sobat) to another station to purchase a ride on a trader’s truck. It would be a full day’s ride (north) to the mountains.

We had purchased a lunch and the driver assured us that he had safe water in a canvas back, hung on the back of the truck. We waited while he loaded the truck and kept loading it until I wondered if there would be enough room for us!

Finally, we were all aboard. I was in front with the driver and both Nellie and Robin. Jessie and David were in the back with Alan. It would be very hot back under the canvas roof. Before we even got started, the driver said the truck had engine trouble and would not be safe. Everything had to be transferred to another truck. It was a very late start, but ultimately, we were on our way.

We sang and talked, watching the giraffes run beside the truck, like rocking horses in constant motion. We saw Golden-Crested Crains doing their mating dances; Ostriches running as though they would miss their train; Guinea Fowl, Water Bucks and hers of all kinds of animals. We even saw a lion, lazily yawing away the day in the little bit of shade he could find.

A stop was called by an out-cropping of rock. We got out and stretched our legs and ate our lunch in the shade of the rocks, very watchful for snakes. Then realization hit us: the truck driver had transferred everything from the broken-down truck to this truck – except the canvas back of water!

It was very hot, and very dry as it was in the middle of the dry season. And we had far, far to go to get to the next town. Alan gathered the children around him.

“We have no water to drink, and it’s a long way until we get to the next town. I do not want to hear anyone say they’re thirsty. Remember Mummy is nursing Robin, so he will be all right. But she will be more thirsty than any of us!”

We got back on board the truck and start off again. We rode for hours in the heat, and my dear children never once said “I’m thirsty”! The driver was very impressed.

The scenery changed to rocky out-cropping’s and hills as we neared the Nuba Mountains. We drove into a small town where there were some Greek traders. Inside of the stores, the driver told our tale. Before you knew it we were drinking Pepsis (Probably Coca-Cola as I doubt Pepsi was available out there back then) – a gift from the traders in greeting. Bottled drinks were much safer from an unknown source. Alan and I were so proud of my children that day.

The villagers gathered outside the store, but we couldn’t communicate very well as they were Nubian, not Nilotic and spoke a completely different language. Some did speak a little Arabic.

Some Sudan United Missionaries came to meet us. How glad we were to see them and were happy to be with our old friends, soon feeling quite at home.

How different the stations were here! They were built near dry riverbeds that, in the rainy season, were filled with raging torrents. Wells near the river provided a good water supply.

Beyond the station, the rocky, steep mountains, often with green valleys between, were such a change for us for we lived on a vast plain with tall grasses and only a few trees ever in sight.

Many villages were right on top of mountains, as in the Ingessana Hills on the border of Sudan and Ethiopia. They settled there for safety from Arab slave traders, which, thanks to Lord Kitchener, was now forbidden. However, living on top of the mountains caused very heavy work for the women, who had to carry up every drop of water used each day.

While we were there, the Sudan United Missionaries held their annual meeting. We had wonderful fellowship and made many new friends, mostly Australians, who later visited us at Obel. We were even asked to speak during their meetings several times. We had so much to share about the growing church in our area.

One day, one of the missionaries came to me in great distress. Her gardener had caught his hand in the water wheel, and it was badly damaged. Deeply cut and crushed, his thumb was almost off.

I had no anesthetic or pain reliever, except asprin, which is a blood thinner – unwise to use in this case! I stitched away for a long tie, patching his hand as best I could. While I was there, I was able to see it heal moverlously.

And later, when we visited the Nuba Mountains again, we went to a leper colony. We were told that we could mingle with the lepers, but they would not expect us to shake hands or touch them. The children stayed in the mission compound. As we talked to those wonderful people, who had almost all accepted Christ as their saviour, I was suddenly aware of a familiar face. It was the gardener I had stiched up! He showed me his hand, quite useful still.

The lepers showd us the church where they all worshipped together, even though they were different tribes. They shared their garden and various occupations that kept them buys, and brought in money for their food.

Every Sunday one lady went a long distance to the villages near town. She had to crawl as she could not walk. She gathered the villagers to tell them of a curse worse than leoporsy: sin, and spoke of a Doctor whou could heal them of their sins, and promised them a home with Him in heave, if they would accept Him as their Savior. They put food out for her, and after eating, she made her painful way back to the leper colongy.

On another memorable visit to the Nuba Mountains, I was resting one afternoon when I was called. A woman had been brought down from a village atop one of the mountains. The family had never been to church at the mission, nor had anyone from that hilltop village. This woman had lost all of her children in previous childbirths, and it appeared that this time she would die unless the baby could be delivered properly. There was no clinic at this station, so, in the fading light of the day, I had them set up the charpenter’s bench and used spears for stirrups. A small lanern was available, but it was not a pressure lantern,so it gave off little light. Fortunately, later there was a full moon.

I examened her, and believed the baby was dead. Her husband said to save her even if the baby was dead. He had other wives to give him children, but this was his first and favorite wife.

I needed forcepts to deliver this child. Alan took the truck and a local missionary to guide him to another station some distance away. There was a good clinic there with what we needed. He soon returned with forcepts, scissors and some medicines. I was able to put forcepts in place, but by then I was very tired. Alan had worked with the red cross during the war and had some medical training in English hospitals. He put his hands over my wrists until I got the baby in position and then he gave me the strength I needed to deliver it. It did seem dead, although I tried for a long time to revive it. My tears showed those people that we really did love them. I delivered the placenta and then gave the mother antibiotics. The husband was so tender and kind to her, and very greatful to us.

We had enjoyed the very different mountainous countryside, but it was now time for us to return to our own station. As we prepared to leave for home, to my delight, the family of the woman I’d atteneded came to church, with half of the hill-top village following behind them.

We carried back wonderful memories of spiritual fellowship in a beautiful part of the Sudan. The dry riverbeds made a marvelous place for the children to play.

They slid in the sand, climbed the rocks, which became their castles, and even hiked up into the mountains with us. They were fascinated by the Arabs and their camels laden beyond belief with cotton bales and other goods that seemed to wander through the mountains.

It had all been a very good holiday!